I was tempted to title this article, “Time to Plantsplain™” I like plants enough to occasionally

hang around exotic plant websites and Facebook plant groups. Probably the most common

question(s) go like this: Why is my plant stretching/yellowing/dropping leaves? The

accompanying pics almost always show plants in rooms, but not in the windows, for example,

“in a bright room 8’ from a southeast window.” And for the gazillionth time, one of us has to

explain that this is just not enough light. So, maybe it is time to review three things

horticulturists need to know about light: intensity, color temperature and duration. I am no

physicist, but we explain this so it is easily understood by the intelligent layperson.

Intensity: Measured in foot-candles or lumens, most of us know that different plants need

different light levels. There are three aspects to consider: location (your latitude), location

(which exposure) and location (where in the room?). Where you live makes a difference—full

sun in Boston is not as intense as full sun in San Jose (that’s Cali or Costa Rica). Which

exposure is important—west-facing windows get afternoon light, so they are warmer than east

windows; south windows are much brighter than north windows (of course, for growers south

of the equator, it is northern light that is more intense). But where in the room? You may not

realize that light intensity falls off as an inverse square of the distance from the source.

Simply put, a plant twice the distance from a light source does not receive ½ the light

intensity--it gets only ¼ the light; 3X the distance gets 1/9, 4X gets 1/16, etc. A simple rule

about light: Healthy houseplants do not grow in rooms, they grow near windows. But

windows have limits; if you have north windows, you really cannot grow cacti unless you are

willing to spend some $$ on artificial lighting (or learn to like aroids). Of course, the reverse is more flexible:

You can grow a spathiphyllum in a big south window—either back it up a few feet or, better yet,

grow it in front of a taller plant! To reiterate, more light does mean more options.

Be conscious of the relationship between light and watering practices. Simply put, the

warmer and brighter the location, the more you will need to water. For example, many people

might think snake plants like it dry. Indeed, a snake plant next your couch or in the meeting

room should be watered sparingly. But the same plant in a big south or west window would

like more water. Also, understand phototropism, the tendency of most plants to grow towards

the light source. Wherever you grow your plant(s), try to rotate at least a quarter-turn every

week to promote symmetrical growth.

For those using artificial lighting, be aware of two things: In fluorescent tubes, intensity falls off

towards the ends. On your light stands, grow higher light plants in the middle, lower light

plants towards each end. Second, because they have a higher surface area-to-volume ratio,

slimmer tubes are more efficient. So T8s are better than T12s, and T5s are better than T8s. I

only use a couple of LEDs, and they are even more efficient than my T5s. Good LED bulbs

are still more expensive than fluorescent tubes, but they last a lot longer. Just as light

intensity is greater closer to a window, it is greater closer to an artificial light. But you need to

careful with flowering plants—an orchid or bromeliad inflorescence can burn too close to a

fluorescent tube. This is another advantage of LED bulbs, which run much cooler.

Which brings us to...

Color Temperature: A concept that will also be relevant for people who grow under

artificial lights (in terrariums or on light stands). Color temperature is a measure of the

proportions of red and blue wave lengths in a light source, measured in degrees kelvin (K).

The redder is called warm, bluer is cool, and even whiter is called daylight. In the old days

growers used to mix red and bluer lights. But with the introduction of Verilux and Vitalite

tubes in the 1980s, growers could have “daylight” in a tube. The original Verilux was 5500K,

which is—dig this—Nebraska on a clear day at noon. Modern daylight bulbs can range from

5000 to 6700K. Some people think that a higher color temp means a brighter light; not so; it

only looks brighter to the human eye because it is whiter. Any fluorescent or LED in the

daylight range are good for most houseplants. Warning: Those of whom keep fish or

frequent pet shops have seen the tubes of 10000K or even 18000K. Never use these on

houseplants—their high color temperatures are designed to penetrate water, in the latter case

for marine corals (the only animals that photosynthesize).

Duration: Is, of course, the time your plant is exposed to light. For most houseplants,

mimicking the seasons is a good rule: 10 hours of light in the winter, 12 in spring/fall, 13-14

hours in the summer. There are a few plants with special requirements. For example, plants

in the morning glory family will not bloom till the days start shortening in late summer; holiday

cacti need long, cool nights in fall to set bud. It is important to understand that increased

duration does not really compensate for lack of intensity. Do not try to grow plants under 24

hour lighting—all plants need some darkness to undergo necessary metabolic processes

(although this may not be possible in some commercial settings).

Try to learn about your plant(s) when you acquire it—plants grown in the right location will be

more vigorous, disease resistant and less like likely to seek advice on Facebook!

Low Light - Spathiphyllum & Pothos High Light - Sago Palm

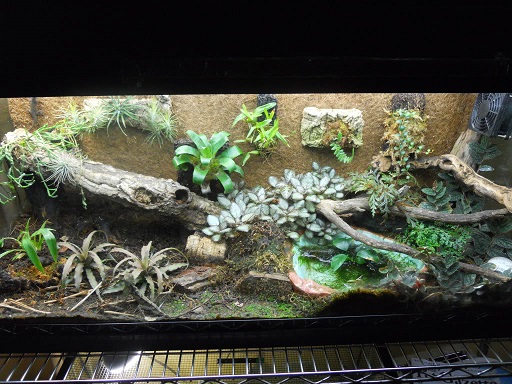

Artificial Light - Mercator Projection